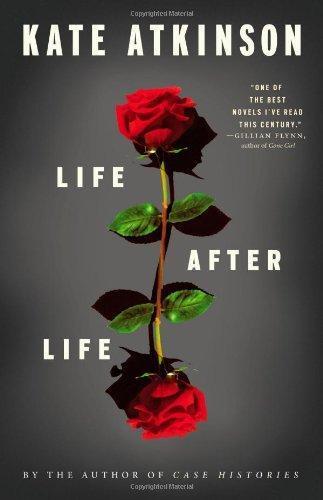

kerry reviewed Life After Life (Todd Family, #1) by Kate Atkinson

Review of 'Life After Life (Todd Family, #1)' on 'Goodreads'

5 stars

Are there some things in life you wish you could do over?

The “plot” of a book can be defined as the sequence of events as presented by the author, and “story” would be the chronological timeline of these events (which may or may not be the same as the sequence presented by the plot).

Atkinson mixes-and-matches plot and story elements in this tale of Ursula Todd, whose births and childhoods and various deaths occur repeatedly. Instead of a linear story, Ursula’s existence appears to be a looped braid or perhaps a Möbius strip, with some elements remaining constant and some details (some subtle, some massive) changing from time to time. But beneath the gimmickry (think Groundhog Day), this is definitely a plotted book; there is a forward momentum even as Atkinson backtracks to tell alternate versions of Ursula’s life.

Is Ursula experiencing déjà vu, parallel universes, reincarnation, time travel, the exercise of free will over fate, or mental illness? Yes. No. Atkinson redefines what all of these terms could mean, and concludes that life consists of the choices we make.

Setting the novel in the first half of the 20th century provides much familiar historical context. Ursula lives (and dies) through World War I, Armistice Day, the flu epidemic, and World War II.

Some basic framework remains unchanged through each life: the family, the household help, the friends and neighbors. Parental figures include beloved father Hugh, opinionated mother Sylvie, aunt Izzie (the “bohemian” one), and benevolent older sister Pamela.

Ursula’s own turn at motherhood occurs during WWII, where her primary focus is on protecting her daughter. Interestingly, the child appears only in this life, which ends with a gorgeous scene that I don’t want to quote here for fear of spoiling the experience for future readers.

Ursula’s romantic relationships are less than fully developed. Some partners persist from lifetime to lifetime, and others (thankfully) are avoided. At least one “what if” scenario is played out (you know, the kind where an adolescent girl moons over some boy she doesn’t really know), and the reality turns out to be less than the imagined. (Not horrible—horrible belongs to a different partner; just less.)

A few observations about the writing style. Sometimes it felt like an exercise (“Come up with 10 ways to kill a character”); and since when is a comma splice acceptable? Early on, when Ursula died more often, it was almost comical (in a bleak sort of way) to have her die over and over. “Oh no,” I thought to myself. “Not again” (even though I knew that was the premise of the book).

I’d recommend this for book club. Even though it’s long (over 500 pages) it’s easy to read.

If you’re more comfortable with stories that depict conventional reality, this is probably not the book for you.

Additional thoughts, hidden to prevent spoilers

Dr. Kellet

Although father Hugh says Ursula is not “defective,” mother Sylvie says Ursula “needs a little fixing” and sends her to Dr. Kellet, a psychiatrist who introduces Ursula to the concepts of Buddhist reincarnation and amor fati, acceptance of one’s fate (what I would characterize as samatha, or calm abidance). Dr. Kellet is a pivotal influence on Ursula; she longs for his guidance several years after she stops seeing him, through several lifetimes, even though Dr. Kellet’s theories seem at odds with Ursula’s experience. He tells the preteen Ursula:

“Perhaps the part of your brain responsible for memory has a little flaw, a neurological problem that leads you to think that you are repeating experiences. As if something had got stuck.” She wasn’t really dying and being reborn, he said, she just thought she was. Ursula couldn’t see what the difference was.

Dr. Kellet continues: “Fate isn’t in your hands. That would be a very heavy burden for a little girl.” The little girl’s burdens are different from the grown-up Ursula’s burdens, so the young Ursula reacts differently, with more impulse, than does the adult, who is able to take a larger view of cause and effect.

I suspect that Dr. Kellet was a lasting influence because he was the only one to take Ursula seriously.

Through Ursula’s multiple lives, Dr. Kellet’s life does have at least one significant variation although he doesn’t seem to be aware of it. Is this change Ursula’s doing, or his own?

Other characters with do-overs?

Ursula gradually comes to realize that she can act to change events – but before she had this insight, how did she come to survive her infancy? My theory is that her mother, Sylvie, also believes in the power of free will. Several times, Sylvie quotes “Practice makes perfect,” and this line also closes out a section near the end of the book, when Sylvie is able to save the newborn Ursula’s life.

(However, an argument against Sylvie’s foreknowledge comes with this passage, when Ursula is a young adult:

Sylvie said, “In the end we all arrive at the same place. I hardly see that it matters how we get there.”

It seemed to Ursula that how you got there was the whole point.)

Perhaps Ursula’s brother Teddy has also figured out the process. Ursula tells him: “You just have to get on with life. We only have one after all, we should try and do our best. We can never get it right, but we must try.” Teddy responds: “What if we had a chance to do it again and again, until we finally get it right?” Turns out that he hasn’t died in WWII so maybe he has the chance for do-overs as well.

And Izzie, who appears to lead a charmed life. Is she getting multiple passes as well? She seems to travel effortlessly from shamed unwed mother to successful author.

Everyone seems to be waiting for something, Ursula thought. “Best not to wait,” Izzie said. “Best to do.”

I’m starting to see every character’s good fortune as a result of intention.

Characters without do-overs

Poor Mrs. Haddock. Her short scenes are identical. She has no insights and lives the exact same life, over and over. Perhaps she’s perfectly happy with everything the way it is – ignorance is bliss?